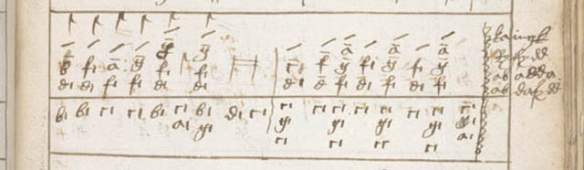

Robert ap Huw: unique binary music

2013 marked 400 years since Robert ap Huw, born in Penymynydd, Anglesey, copied out his manuscript of bardic harp music cerdd dant (the earliest European body of music expressly for the harp) containing hours of music. This is the only source of Welsh bardic cerdd dant music, some of it considered to date from the 14th century. The music is written in an unique tablature for the harp and is unlike the folk or classical music played in Wales today. It requires the harpist to use long fingernails and to pluck and damp the strings according to a strict system. The harmonic language is not the one used today but a binary system contrasting two sets of notes.

‘Bardic’ pertains to medieval Welsh professional poets, harpists, crwth players and specialist singers – ‘datgeiniaid’. Organised into guilds, they created, memorised and performed high-art poetry and music to immortalise their patrons in a ritual setting and continued working in Wales till the end of the 16th century. In late-medieval Wales only the crwth and harp were considered bardic instruments. There are social, theoretical and technical parallels between the bardic professions of Wales, Ireland and Scotland.

Bardic professionals learned huge repertoires aurally. Wiliam Penllyn’s realisation, earlier in the 16th century, that bardic life was coming to an end probably prompted him to devise a tablature and write down bardic harp music, cerdd dant, for the first time. His lost manuscript is Robert ap Huw’s likely source.

By the time Robert ap Huw completed his training, bardic poetry and music were no longer valued. He practiced his profession, briefly, in North Wales at the end of the 16th century, fell foul of the law, was imprisoned, sprung from jail, disappeared, then reappeared at the court of James I.

Robert was trained to play the bray harp telyn wrachod/wrachiod, the harp played all over Europe, except for Ireland. Brays are pieces of wood fitted to the harp at every string hole, securing the knotted string to the belly of the harp. More importantly, they are angled to touch each string lightly, as it vibrates, and designed to produce an intense, buzzing sound, radically different from the pure tones valued today. This was not crude: it created the richest texture of harmonics. In the late-17th century the bray harp was known in England as ‘the Welch harp’ and was played in Wales till 1815. Each technique indicated in the Robert ap Huw manuscript elicits different tones from the harp.

‘Precise, angled brays / Speaking every profound feeling.’

‘Ceimion wrachiod cymmwys / Yn siarad pob teimlad dwys.’

(From a cywydd requesting a harp by Huw Machno c. 1560-1637)

This music was no mere entertainment (though it might cause delight). Its purpose, together with praise poetry, was to immortalise the people who paid for it. Bardic performances were part of the social ritual of late-medieval Welsh life. The performance of a new praise poem, together with poetry commemorating the patron’s ancestors demonstrated his wealth and discernment, establishing his lineage and status before his superiors, peers and inferiors. Contemporary powerful Englishmen commissioned paintings, palaces, church music and chapels to ensure their immortality.

The last thirty years have seen a great development in bringing the medieval and later bardic music of Ireland, Scotland and Wales back to life, using historically-informed principles i.e. seeking the oldest sources of notated music and theory, using careful copies of contemporary instruments and using the playing techniques and tunings prescribed in historical documents. Recombining bardic poetry cerdd dafod with string music cerdd dant requires collaboration with scholars of medieval literature. These developments would be impossible without the work of dedicated instrument makers.

Bardic music cannot be played using modified modern instrumental techniques. A harpist or violinist must learn to play the bray harp or crwth from scratch, renouncing the techniques and sound-world of Welsh folk or modern classical music.

Living traditions from elsewhere may be more instructive than Welsh folk traditions e.g. Bosnian epic singing, praise traditions from West and East Africa (with striking formal similarities to Welsh bardic music) and Asian epic performance.

To celebrate the 400th anniversary in 2013 the voice and crwth duo, Bragod, created a show ‘Adar/Birds’, a concert of poems by Dafydd ap Gwilym and ‘Ymddiddan Arthur a’r Eryr’ (‘Arthur’s Talk with the Eagle’) set to music from Robert ap Huw’s manuscript. For information on this or about Robert ap Huw and his music, see www.bragod.com or bragod.wordpress.com

Article by Robert Evans and Mary-Anne Roberts