Leila Salisbury on Wales’ first folk song collector

Those of us who study, perform and take an interest in Welsh traditional music, could not visit the National Eisteddfod in the Vale of Glamorgan without considering the contribution made to that tradition by one notable fellow, over two hundred years ago. That colourful, audacious and playful character was Iolo Morganwg. Today, Iolo is considered the first collector of folk songs in Wales. He was the first person to record the songs of his local area and set them down on paper, the first to record the social context of the melodies and the first to realise the value of this fragile oral tradition. Iolo recorded the folk songs of the Vale of Glamorgan between 1795 and 1806.

While visiting the National Eisteddfod, linger awhile to imagine the scene that Iolo would have seen, on the threshold of the nineteenth century. In those days young lads would plough the land, leading their yoked oxen, and singing triplets behind them so as to encourage the animals to press forward. The triplet was a measure that appealed greatly to the inhabitants of the Vale of Glamorgan of the period, and particularly perhaps to the ‘ox-drivers’ of Glamorgan. This – cathreiwr – was the term used in the southern counties for a person who sang to oxen, the corresponding term in the north of Wales being ‘geilwad ychen’, or ox caller. Iolo recorded a number of the Glamorgan triplets, including this one:

Merch ifanc deg ei dwyfron,

Yw’r un a gâr fy nghalon,

Does bwyll na synnwyr yn fy mhen,

Ond sôn am Wen lliw’r hinon.

(A fair breasted young maiden

is the one beloved by my heart,

all care and sense leave my head

when mention is made of lovely Gwen)

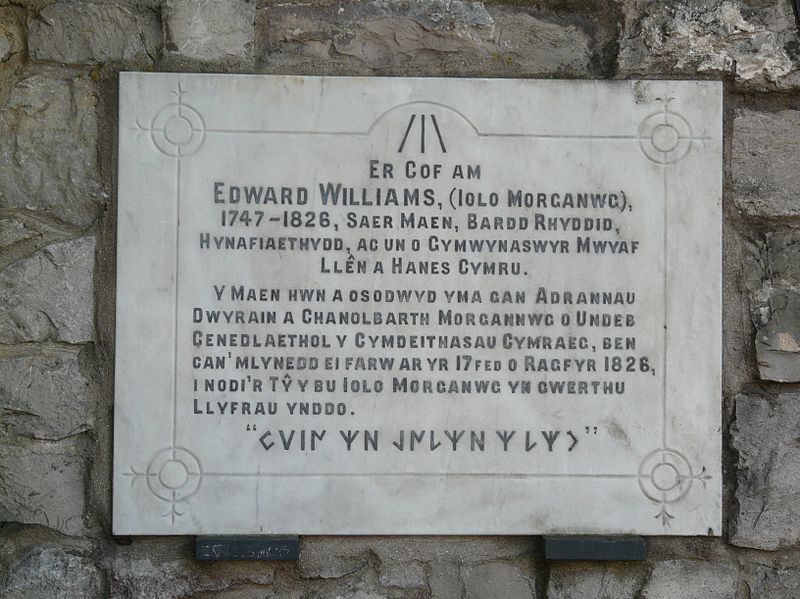

Iolo was born in Pennon, in Llancarfan parish, on the 10th of March 1747. In 1754 the family moved to Flemingstone, where Iolo and his family remained for the remainder of his life, up until December 18th, 1826. If you happen to travel through Cowbridge you’ll see, opposite the Hall clock on the High Street, a plaque on the wall (pictured below) commemorating the location of Iolo’s bookshop.

Of the 88 folk melodies recorded by Iolo, some with and others without words, nineteen are associated with seasonal celebrations (such as May Day, Christmas, and Wassail singing), fifteen can be categorised as love songs (which make reference to the ancient traditions of love-messenger songs and praise singing), ten are occupational songs (for example, ox driving songs and milking songs), and the remainder are a variety which refer to everyday characters and ordinary situations.

As you will see from the contemporary illustration, Iolo would wander the area on foot, his pocket book in one hand and his stick in the other. He recorded a number of the folk songs in this little book which bears the official title ‘Casgledydd Penn Ffordd’ (nowadays, this book can be seen at the National Library in Aberystwyth). This collection bristles with comments and explanatory notes in Iolo’s handwriting, and also includes, of course, his own melodies which are themselves a valuable source for the ordinary reader eager to discover some of the mystery and romance that surrounds these melodies.

As you will see from the contemporary illustration, Iolo would wander the area on foot, his pocket book in one hand and his stick in the other. He recorded a number of the folk songs in this little book which bears the official title ‘Casgledydd Penn Ffordd’ (nowadays, this book can be seen at the National Library in Aberystwyth). This collection bristles with comments and explanatory notes in Iolo’s handwriting, and also includes, of course, his own melodies which are themselves a valuable source for the ordinary reader eager to discover some of the mystery and romance that surrounds these melodies.

Sometime later, Iolo’s vision led to a renaissance in the history of Welsh folk music. Following his example of collecting and recording aspects of the folk singing of his time, by the early decades of the nineteenth century others came to appreciate the value and power of keeping a hold on, and chronicling, oral material. In the face of the great social, agricultural, industrial and musical changes of the times, local, oral traditions would undoubtedly have been lost. Our debt to the assiduous work of the collectors and the antiquarians of yesterday is great.

Today we have in Wales the National History Museum at St Fagan’s and a National Library, which serve as repositories for the treasures of the past and as a place to keep records of the old customs, the old manuscripts and the old melodies. But in Iolo’s day, such establishments were mere dreams. At that time, collecting and safeguarding history, songs, poems and so on was a new concept and the responsibility for doing so was, more often than not, in the hands of individuals. Theirs was a priceless labour of love on behalf of the generations of the future. Certainly, without the work and perseverance of people like Iolo, our heritage and musical tradition would be all the poorer.

by Leila Salisbury

Article first apppeared in Ontrac magazine when the Eisteddfod came to the Vale of Glamorgan in 2012.

Below: Stephen Rees sings one of Iolo’s collected songs; a contemporary portrait; the plaque in Cowbridge at the site of his old shop (now a Costa Coffee); and a giant Iolo Morganwg presiding over 2014’s Beyond the Border international storytelling festival at St Donat’s Castle in the Vale of Glamorgan.